Please note that I’ve moved all ‘Missing 3,000’ content to my new blog: H.E. Watch

Thank you

Steve

In 2012, following a near-trebling of student fees in England, recruitment fell by 9%.

However, 2013’s headline is that normal service has now been resumed. Indeed, entry levels are close to a record high.

This is good news for all. That HE brings both individual and societal gains is well established. Rumours persist that participation may even offer the odd cultural benefit, though ‘public good‘ remains a phrase conspicuously absent from most wider discussions of HE.

History will also record 2013 as the year in which the mature student began heading towards extinction. Application rates for those aged 21 or over have fallen 14% since the fees hike, and there’s little real hope of recovery. (Note that the graph below covers only 18-year-old applicants.) Prospects look similarly bleak for would-be UK postgraduates.

On a more positive note, the 2013 National Student Survey found undergraduates to be happier with their lot than ever before. A blunt instrument though the NSS is, it would be churlish to argue that the ‘student experience’ hasn’t improved since its launch in 2005. 85% of graduating students are satisfied with their degree programme.

With universities now all REF‘d out, the pendulum is likely to swing back towards teaching. For England’s 1.5 million £9k-a-year paying undergrads, this can only be good news.

Private universities continued to be welcomed into the English HE market, though the New College of the Humanities fell short of its very modest recruitment targets once again. Three-quarters of its £18k-a-year paying students attended an independent school.

Such was demand elsewhere, however, the government was left with a black hole in its budget. With plans to sell off the student loan books being likened to a Ponzi scheme, some wonder why we seem intent on following the US down the path of bubbling, unsustainable student debt at a time when Germany are abandoning their fees experiment altogether.

Sadly, 2013 saw the demise of the 1994 Group. Meanwhile, the University Alliance’s end-of-year message raised eyebrows by commending the government for courageously taking the “economic and moral high ground” (my italics). It also raised questions about what exactly HE mission groups and consortia are for.

Politically, Willetts and Cable continue to pull the strings, while Graduate Tax advocate Liam Byrne replaced Shabana Mahmood as Labour’s Shadow HE minister.

Universities UK got told off by Polly Toynbee for suggesting it’s okay to segregate female and male students, and Sussex Uni quickly reversed its decision to suspend five students for protesting peacefully.

In terms of WP, the proportion of poorer students applying for university held firm, though ‘top’ universities continue to recruit at much lower levels than other institutions.

According to a Sutton Trust report issued in November, at least one quarter of this “access gap” can’t be attributed to academic achievement, further evidence that there may be more to Russell Group under-representation than A-level performance.

And what to expect from 2014?

Well, English universities will soon be able to take as many students as they like. That’s good news for many, but it could increase the pressure on struggling institutions to maintain market share as their sought-after WP students are lured elsewhere.

Universities free from recruitment anxieties will continue to press for the £9k cap to rise.

Meanwhile, early applications figures for 2014 are down 3% on the same time last year.

Long-term, it may not be the headline £9,000 figure that’s most damaging to the HE sector.

Rather – as I’ve argued elsewhere this year – a bigger problem could be continued uncertainty about the security, fairness and expense of the student loan system itself.

“Like applying a bandage to lung cancer.”

That’s how Dr Martin Stephen last week described the idea of allowing disadvantaged students into top universities when they’re an A-level grade or two below the usual threshold.

Dr Martin Stephen is a former chairman of the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference (HHC) and ex high master of St Paul’s School in London. He was responding to Bahram Bekhradnia expressing dismay that, in his time as director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, the top universities had remained “as socially exclusive as ever“.

Mr Bekhradnia suggested that the UK should follow US institutions’ lead in seeking to create cohorts that “represent wider society as far as possible,” obsessing less about academic attainment at the point of entry.

For Dr Stephens, such a move would let low-achieving schools ‘off the hook’. It’s social engineering gone made, or whatever.

“Our schools are not helping disadvantaged children to achieve respectable grades and these things don’t do anything about that problem,” he complained.

There are several problems with this position. First, a good deal of one-way evidence tells us that state schools pupils actually outperform independent school students once they reach university. Second, we know that state school applicants are less likely to be offered a place at Russell Group universities than independent school applicants with the same grades, even when ‘facilitating subjects’ are controlled for. Third, it is questionable whether low-achieving schools are incentivised by their students’ progression rates to top universities in anything like the way Dr Stephens implies.

But more disturbing than the views being represented are the metaphors increasingly being traded by those with vested interests.

Is academic under-performance, and the schooling system responsible for it, really like lung cancer? Or are such schools actually working hard to raise attainment among young people with multiple disadvantages, social problems and often chaotic home lives? The latest PISA findings suggest that socioeconomic background is the key determinant of educational success, not school type.

Note the similarly belligerent response to a recent report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, who found that England’s grammar schools were now four times more likely to admit private school children than those on free school meals. This time it was the turn of Robert McCartney, chairman of the National Grammar School Association (NGSA), to return fire:

“Many, many parents from deprived areas, including what is generally called the dependency classes, are essentially not particularly interested in any form of academic education,” said Mr McCartney. “Their interests are directed towards pop culture, sports.”

Naturally, the HHC, NGSA and other such organisation are bound to defend their market edge. Many independent and selective schools actively recruit on promises of entry to prestigious universities.

But should this defence spill over into unsubstantiated slurs against those from less advantaged communities? Poorer parents share the same aspirations for their children as their wealthier counterparts. It helps no-one to liken low-attainment schools to horrible diseases.

Let’s debate the evidence and leave the name-calling in the playground.

Revisiting Debates about the UCAS Personal Statement

This post was first published on Oct 14th 2013 by “Manchester Policy Blogs“.

With the first UCAS deadline of the academic year looming, thousands of University hopefuls are putting the finishing touches to their personal statements. But growing evidence points towards the current process favouring some applicants more than others – and it may be time for a radical overhaul, according to Dr Steve Jones.

“The UCAS personal statement is academically irrelevant and biased against poorer students,” ran the headline of one Telegraph blog last month.

According to its author, paying a private company to write your statement now costs between £100 and £200, and the whole thing is little more than “an exercise in spin”. Meanwhile, The Times report that tutors “often ignore students’ personal statements,” describing the indicator as “worthless”.

Perhaps more significantly, last week saw the publication of a Pearson Think Tank report called “(Un)Informed Choices“. The executive summary was surprisingly frank in its recommendation: “the use of personal statements should be ended.”

The debate has interested me since I was commissioned by the Sutton Trust last year to collect new evidence about the personal statement.

My findings were stark. Basic writing errors (like misspelling and apostrophe misuse) were three times more common among applicants from state schools and sixth form colleges as those from independent schools. There were also big differences when it came to work experience: independent school applicants had lots more, and it tended to be high prestige.

All of the statements I looked at were written by students with the same A-level results, so I wondered whether the textual differences offered a partial explanation for the unfair outcomes reported in UK admissions processes more broadly.

For example, research at Durham University has shown that state school applicants are only 60% as likely to be made an offer by Russell Group universities as independent school applicants with the same grades in “facilitating” subjects.

So why hasn’t the personal statement been binned by UCAS already? In my experience, there are five main lines of defence:

1. “Admissions Tutors aren’t taken in by slick expensive personal statements”

This was the response of Cambridge University’s Prof. Mary Beard to my research, and I think it’s a very reasonable point. Any experienced reader of statements will have well-honed “crap detection” skills. Who’s to say our admissions tutors aren’t seeing right through the fancy work placements and LAMDA successes? The problem is, as a sector, we’re neither consistent nor transparent in how personal statements are read. Sometimes they’re given close, critical attention; sometimes not. Either way, we keep schtum about the criteria we use and the weight we attach to them.

2. “There’s never an excuse for spelling mistakes, is there?”

This point was made to me twice by a BBC TV newscaster. The answer is no, there’s never an excuse. However, if you have lots of people to proofread your statement and you’re repeatedly told it’s something you’ve got to get right, chances are you’ll take a bit more care. The sixth form college applicant who made twelve basic language errors in his statement wasn’t stupid – his attainment record proves that – he just didn’t understand how much those mistakes could count against him.

3. “We like to be holistic in the way we select our students”

It’s never easy to argue with the word ‘holistic‘, but there’s no advantage to using lots of indicators unless every one is bringing fairness to the selection process. Perhaps a small amount of appropriately contextualized attainment evidence is actually more equitable than a wide range of hazy non-academic indicators?

4. “We use the personal statement as a starting point for interview questions”

The Oxbridge colleges sometimes use this argument, but it isn’t a very strong one because most UK university applicants aren’t interviewed for any of the degree programmes to which they apply. And, for those that are, surely it’s not beyond interview panels to formulate their own questions? Besides, the most elite universities are often the sniffiest about statements: we don’t want “second-rate historians who happen to play the flute,” says Oxford’s head of admissions; “no tutor believes [the personal statement] to be the sole work of the applicant any more,” says his former counterpart at Cambridge.

5. “Actually, we know personal statements aren’t a reliable, and we don’t bother reading them”

This point is made regularly, but with half a million statements written every year, maybe it’s time someone mentioned it to the young people who stress and sweat over writing them?

There’s room for compromise, of course. In 2004, the Schwartz Report suggested redesigning the UCAS application form to include prompts that elicit more directly relevant information in a more concise fashion. Those applicants with the social and cultural capital to secure the best work experience and highest prestige extra-curricular experience would then have less opportunity to cash in on their good fortune.

But for the last word on the subject, here’s a member of admissions staff (quoted anonymously in the Pearson report) on just how much difference school type can make to the personal statement:

“I’ve spoken to heads of private schools about the question of how much help they give students in writing statements. They say ‘well, they’re paying £7,000 a term, of course we give them a lot of help, that’s what they’re paying for’. And yet you see statements from what [are] potentially good students from schools which have not got a lot of experience of sending their students to HE, and they’re not very good because no-one knows what to do, how to do it.”

University as a ‘public good’? Only for those who never went…

This post, co-authored by Anna Mountford-Zimdars, was first published on Oct 4th 2013 by “British Politics and Policy at LSE“.

Using data from the last 30 years, Steven Jones and Anna Mountford-Zimdars examined public attitudes towards participation in higher education. Despite questions being framed in ways that increasingly constructed university as a public expense, they identified a persistent belief in the core values of Higher Education. Among some of the surprising results, they found that graduates were more than twice as likely to favour a reduction in participation as non-graduates.

In an era of rising tuition fees, deepening student debt and the global commodification of learning, any remaining notion of Higher Education as a ‘public good’ may seem improbable. However, evidence from the British Social Attitudes survey shows that the broader, society-wide benefits of Higher Education are still prized, albeit not always by those you might expect.

Together with colleagues from Oxford and London University, we examined surveys from the last thirty years to chart how public attitudes towards participation have reflected changes in policy. Despite questions being framed in ways that increasingly constructed university as a public expense, we identified a persistent belief in the core values of Higher Education. For example, 43% of those surveyed in 2010 thought that over half of young people should go on to university, a finding at odds with popular perceptions of a labour market saturated by graduates of ‘Mickey Mouse’ degree programmes.

More surprising, Higher Education was cherished most highly by those from lower social classes. Only 10% of working class respondents thought opportunities should be reduced, compared to 26% among the professional and managerial classes. We also found gender and school type to be key predictors of attitude. Men were more likely than women to say that university isn’t worth the time and money, as were those educated privately. But the strongest predictor was whether respondents had themselves participated, with graduates more than twice as likely to favour a reduction as non-graduates. Those who profit most from Higher Education, it would seem, are those most inclined to pull up the ladder behind them.

Of course, such are the private benefits of Higher Education for many graduates that public funding for universities could be regarded as little more than a middle class subsidy. However, this frames debates within the narrow, individualistic terms of human capital, problematic not only because different degree programmes yield different income ‘premiums’, but because, for some students, the value of a degree isn’t solely economic – it’s also about personal growth and the chance to become part of a better-educated, fairer society.

Self-interest is increasingly assumed to be the main driver for Higher Education participation, with students constructed as savvy consumers and debt justified in terms of enhanced lifetime earnings (or repayment concessions for those less fortunate). But against this tide of marketisation, support for Higher Education as a public good lingers.

Full paper: Anna Mountford-Zimdars, Steven Jones, Alice Sullivan & Anthony Heath (2013) “Framing higher education: questions and responses in the British Social Attitudes survey, 1983–2010”. British Journal of Sociology of Education (34, 5-06), pp. 792-811.

Coinciding with the publication of this summer’s exam results was a familiar spate of media pieces warning universities not to “patronise poor kids” by lowering offers to those who don’t get the grades.

As usual, such students are constructed as a “gamble”, universities as well-meaning but naïve institutions, and OFFA as meddling social engineers. The “real” problem always lies elsewhere.

But is it really an academic “gamble” to acknowledge that not all young people have the same schooling advantages?

No, says most of the evidence. Primarily because such students actually outperform those from the private sector once at university. In fact, to recruit on grades alone would be a far greater gamble – that’s why most universities now consider contextual data when choosing between similarly qualified candidates.

In this week’s TES, Tom Bennett argues that such approaches simply move the injustice elsewhere, “from lack of opportunity for some from birth, to lack of opportunity for some at the point of university admission”.

This is a quite a claim: that advantaged students, often brimming with social capital and coached to game the HE admissions system, could face a “lack of opportunity” at the Russell Group gates.

I’m not sure we need worry about that just yet.

Indeed, using a Freedom of Information request, The Guardian last week showed that private school applicants were 9% more likely to be admitted to Oxford than those from state schools with same grades. Long-term academic studies of UCAS data reach similar conclusions.

Put simply, applicants from the state sector must earn higher grades than their private school counterparts to have the same chance of entry.

This is generally lost on the authors of topical opinion pieces, where the approach tends towards “I know of one student…” anecdotes.

For Bennett, “universities are not places in which to unpick the stitches of historical injustice”.

But if those stitches need unpicking, where better to start?

Earlier this week, under the headline “Universities fix results in ‘race for firsts‘”, the Telegraph reported on research by Prof John Thornes of Birmingham University suggesting that the rules according to which degree classifications are calculated were “often bent to boost numbers”.

In short, undergraduate students are now twice as likely to be awarded a first or an upper second than they were in 1997.

Interestingly, the odds of GCSE students achieving a top grade have only risen by about a quarter (from 54.4% to 69.4%) over the same period. From this, one could conclude that degree awards are inflating four times faster than GCSEs.

Here are some other alarming stats about ‘award inflation’:

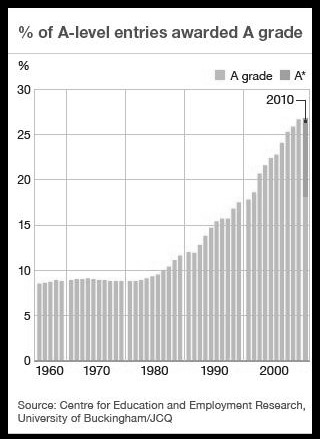

In the UK, we’re all familiar with debates about grade inflation in pre-18 education. “They didn’t have dumbed-down exams like that in my day” is how some will respond to the graph below. For others, it’s simply evidence that teachers have got better at teaching and learners better at learning.

Naturally, the marketisation of HE puts pressure on universities to be more generous in their awards. “How many firsts were there last year?” parents ask at Open Days. League tables rank institutions on the proportions awarded.

A further problem is that universities have different ways of calculating degree classifications. I’ve attended (and chaired) dozens of Exam Boards, many as an External Examiner. Regulations differ, and grey areas can usually be found. Some Boards take performance across all years of study into account; others don’t. Some discount a student’s lowest score; others factor in ‘exit velocity’ for those who perform strongly in their final semester. Most have a system for identifying ‘borderline’ students; some even have a separate policy for ‘borderline borderlines’.

No academic wants to disadvantage their own students. It’s little wonder that awards creep higher each year.

Alternatives aren’t easy to find. University College London recently announced they would abandon traditional classifications for an American style “grade point average”. This is a far preferable solution than that proposed by Prof Alan Smithers of Buckingham University, who wants to introduce a “starred first” (to be followed, presumably, by a double-starred first, then a triple-starred first…).

So why does ‘award inflation’ receives less media attention than its naughty younger sister, ‘grade inflation’?

Cynics might suggest that if everyone does better in their GCSEs and A-levels, the established middle classes don’t like it because their educational edge is eroded. However, if everyone does better at university, this doesn’t matter so much (because by then most of the working classes have been filtered out the system anyway).

There’s a touch of conspiracy about that theory, but – whatever the explanation – I can guarantee that the next time you read about qualification inflation, the story is more likely to be about school children than university students.

A couple of weeks ago, The Guardian leaked a confidential, Whitehall-commissioned report, written by Rothschild investment bank and piss-takingly dubbed ‘Project Hero’.

‘Project Hero’ proposed redrawing the terms of student loans taken out over the past 15 years to make them more expensive for borrowers and therefore more attractive to potential purchasers.

Danny Alexander (Chief Secretary to the Treasury) later confirmed that the student loan book will indeed be privatised to raise £10bn, but offered no further details about the ‘sweeteners’ involved.

Among the first to respond was Martin Lewis, head of the Independent Student Finance Taskforce. Lewis has succeeded in explaining higher fees to the younger generation better than any politician or university, so it’s interesting that he went off-message and took a strong stand against the suggested fire-sale, tweeting:

“To hike past students loan interest [would] betray every democratic principle and kill confidence in loan system.”

Lewis’s point is a very good one. It’s an act of faith for anybody to attend university in the higher fees era. Trust in the loan system is vital. Any suspicion that graduates will be fleeced by the state is likely to have serious consequences, especially for the most debt-sensitive of young people.

Writing in The New Statesman, Alex Hern has been excellent at explaining the economic ramification of the sell-off, first describing the idea as “terrible financial management” and then noting that:

“Our government is twisting itself in contortions, discussing student loan debt as though it’s a pile of newspapers sat at the back of the treasury, which they mustn’t be “compulsive hoarders” of, in order to sell at a discount an asset which is significantly more valuable in public hands than private. It’s politically driven economic illiteracy.”

Finally, Tim Whitmarsh, a Professor of Ancient Literatures at Oxford University, makes important points about social justice:

“The situation is deeply troubling. Higher education is the primary driver of social mobility in the UK. Huge fees are already a deterrent to many, but at least when they came in we were promised a benevolent, progressive loans structure. The involvement of the private sector in student financing can only damage that. Private companies want profits, and profits have to come from somewhere.”

Professor Whitmarsh has set up an online petition against loans privatisation, which already has over one thousand signatures. It can be found here.

All three of the arguments above are very persuasive. Nothing will undo Lewis’s work in promoting the new system faster than potential university students losing confidence in those from whom they must borrow. Hern is also right to point out the mindless economic short-termism of the proposal. And Whitmarsh’s concerns about interfering with the ‘safety net’ of a relatively progressive clawback mechanism are entirely justified if participation rates, particularly among those from less well off backgrounds, aren’t to be damaged.

As Martin McQuillan says, this is a “trainwreck” of an idea.

For an overview of the counter-arguments to this position, see Andrew McGettigan’s patient summary of a sell-off’s ‘quick wins’. However, note that McGettigan’s conclusion – that selling the loan book “without consent or consultation and without a parliamentary vote” is not on – is entirely consistent with the views expressed above.

The terms of students’ participation ‘bet’ must always be honoured. If you back a winner at 3-1, you don’t expect the bookie to ‘retroactively’ cut your odds to 5-2.

You can’t change the price of a degree once the student has graduated.

I’m just home from this year’s Festival of Education, at which I was fortunate enough to be asked to speak.

The experience was a very positive one, and I met many new people with terrific new ideas about the future of education. It felt strange to be giving a presentation about young people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds in the grand setting of the College’s Old Hall, but the audience response was among the most favourable I’ve ever had.

Some of the other talks were outstanding, as blogged here, here and here. Of the politicians, it was interesting to hear Lord Adonis note that private schools “do well by the taxpayer”, but I wasn’t too convinced by his idea that stay-at-home students should get half-price degrees. Tristram Hunt did his best to outline a Labour alternative to the coalition agenda, and criticised government dismissiveness towards teachers and educational professionals. David Laws pushed for schools to be graded according to their success in closing the disadvantage gap, putting up a strong defence of the pupil premium. And I was pleased to hear Michael Gove acknowledge the role that social capital plays in university admissions processes.

The only session I didn’t enjoy fully was a panel entitled “What do we want our children to know?”. Anastasia de Waal and Mark Thompson were excellent, making a series of observations that were measured, constructive and engaging. But Toby Young was provocative for no good reason (as is his wont), referring to child-centred learning as “balls” despite appearing not to understand what it actually involves.

The fourth panelist, Lindsay Johns, was amusing in his views about “dead white men” in the curriculum (have more of them!) and refreshingly honest about how teachers should relate to pupils (stop listening to them!). I was reminded of his controversial take on Oxford University’s decision to admit only one student of Caribbean origin in 2009.

But then Johns started condemning what he calls “ghetto grammar” (the symptoms of which include “vacuous words such as ‘innit’ and wilful distortions like ‘arks’ for ‘ask’,” according to an earlier piece in the Evening Standard). As a time-served linguist, I felt obliged to raise my hand at the end. The dangers of stigmatizing ‘street slang’ have been compellingly outlined elsewhere, and Lester Holloway has flagged up broader problems with Johns’ position. So all I did was point out that the way a young person speaks is often inextricably tied up with their personal identity. Rather than correct non-standard usage, I suggested, a more productive alternative might be to have pupils reflect on all that’s grammatically and phonetically distinctive about their own dialect. That way they learn about the conventions of Standard English without being made to feel inadequate for speaking a non-standard, though often equally systematic, variety.

This was my only grumble about an otherwise fascinating event. At Wellington College, I learnt much about the key debates within Education, and often found my preconceptions challenged and values tested. The Festival brings together people with all kinds of perspectives and covers a range of important issues. A few more state school teachers need adding to the mix, and a third day of events would make the journey more worthwhile, but I couldn’t help but be impressed by the originality of the thinking and the commitment to the cause.

Last month, I was lucky enough to speak at the American Educational Research Association’s annual conference (AERA13), where the theme was Education and Poverty. Some of the research presented was utterly compelling: carefully-collected, long-term, large-scale empirical evidence, all pointing towards growing inequality of opportunity. Young people are hungry for education, the argument went, but the US schooling system lets them down.

In the area I’m most interested in – access to higher education – several speakers talked compellingly about the problems faced by first generation applicants in accessing financial aid, getting appropriate advice, and negotiating the admissions process. The conference also screened a number of films, including this brilliant one about four ‘undocumented’ students and their attempts to reach college.

The visit of US Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, was most controversial. Protests took place outside the venue and, inside, Not In My Name flyers were waved throughout. Duncan’s love of school testing does not sit well with AERA members. His defence was “Chicago-style nonsense,” according to one entertaining report.

The conference wasn’t all downbeat. Delegates clearly wanted to make education a fun and productive time for all young people. Social media was repeatedly cited as possible social leveler, gaming as a fresh way to engage young people on their own terms, and wrap-around policies as essential for less advantaged children.

At times, I wondered what the conference would make of educational policy in the UK, which seems not only to ignore empirical evidence but to purposely move in the opposite direction? Without wishing to generalise, AERA seems more politically aware (or maybe just political) than BERA.

I left thinking that if Obama’s Duncan gets this much stick, maybe us UK educationalists go a little too easy on Cameron’s Gove?